By now, you’ve probably already learnt that medical school is tough – and will probably be one of the toughest things you’ll ever do.

You have a short amount of time to pack in and process an absurd amount of information. The expectations are high. Med school has an environment that can put a strain on the mental wellbeing of even the most well-prepared students.

As a result, success at med school is likely going to have to involve some changes in how you approach your studies.

Less preparation creates more stress, and more stress can create less preparation, culminating in a stifling feedback loop that eats away at your performance and mental wellbeing alike.

What may have worked for you as an undergrad probably won’t cut it, now. Your past successes as a student are no indication of how well you’ll do in medical school. Indeed: time management, stress, and preparation will be better indicators at med school.

A little stress is motivating, but excessive stress can negatively affect your performance. A 2020 study by researchers at China Medical University confirmed this, finding that much of the anxiety med students experience stems from a lack of preparedness, a factor that can become compounded by the stress.

Less preparation creates more stress, and more stress can create less preparation, culminating in a stifling feedback loop that eats away at your performance and mental wellbeing alike.

Start with a strategy

The preparation required to end this vicious cycle has to be done with purpose. Start with developing a proven learning style that puts an emphasis on organization, preparation, and optimized time management.

As a 2011 study from Texas A&M put it: “improving the prioritization and organization of study time and teaching students to predict, compose and answer their own questions when studying may help to advance student performance regardless of student aptitude.”

Let’s break that down and focus on three key parts of a good study strategy: routine, a study schedule, and meaningful downtime.

Routine

Waking up with little idea of what the day holds or what is expected of you leaves plenty of room for feelings of anxiety to seep in.

To remedy this, you need to set some positive patterns in your life so your expectations are clear and each new day is mapped out and waiting to be seized.

You’ve probably heard throughout your life the importance of developing good habits. The difference now is the degree to which your days will be planned. Setting this routine shouldn’t just be a thought exercise.

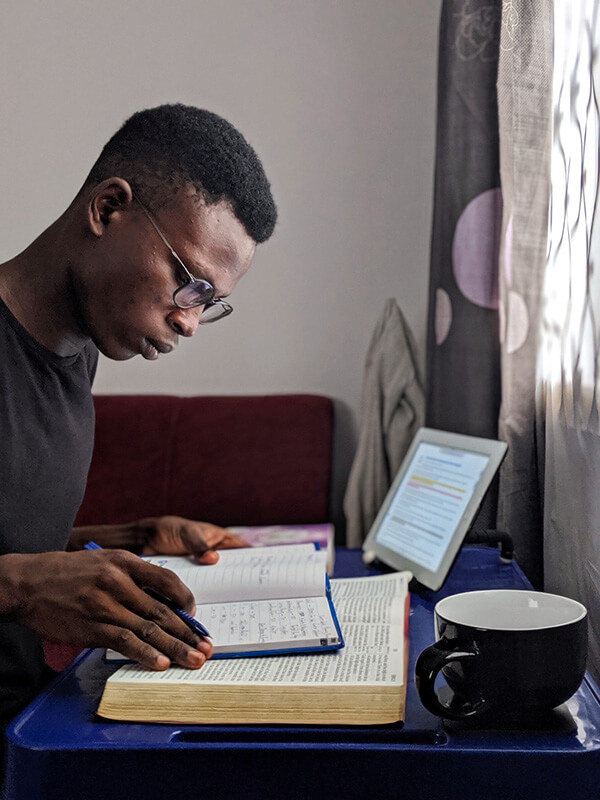

Go ahead and break out a pen and paper (digital ink works, too). Blocking out study times is important, but don’t leave out things like meal times, errands, playing with your cat, and—most importantly—sleep.

… med students who don’t get enough good-quality sleep might find it difficult to focus on the complex information that they are learning for sustained amounts of time during their lectures.

According to Dr. Erin Ayala at Saint Mary’s University of Minnesota, one of the co-writers of a study on sleep and medical students, “med students who don’t get enough good-quality sleep might find it difficult to focus on the complex information that they are learning for sustained amounts of time during their lectures.”

We know you’re busy, and burning the midnight oil might be unavoidable, but where possible, schedule what you can during daytime hours. This has been shown to help mental health, and every little bit counts.

Study schedule

As you map out your daily routine, go deep on the time you’ve blocked for studying. Put it all on a physical (or digital) calendar. Consider which topics you should be focusing on each day leading up to the exam.

Do they build logically on each other? Are you setting aside days to challenge what you’ve learned? Are you giving yourself adequate rest days so your brain has some space to process everything?

Meaningful downtime

We cannot overstate the importance of working rest days into your routine and study plans. They aren’t just a nice break, they form a key part of any successful study strategy.

Rest days have been shown to help you avoid burnout, a problem affecting around 53 percent of medical students in the US. The truth is that the pressure you may feel to work harder and longer than everyone else is more likely to hinder your ability to reach your goals, rather than help it.

A 2017 study found that “longer working hours are associated with poorer mental health status and increasing levels of anxiety and depression symptoms,” adding that anxiety is likely to manifest itself in some counter-productive ways, including poorer performance on these make-or-break exams.

It’s going to take a cultural shift to break this deeply ingrained “all work all the time” attitude.

It’s much more effective to work smarter than harder. As a med student, you already have enough to do. Dr. Williams, founder of OnlineMedEd, put it best: “You will work. Don’t forget also to live.”

Your mental wellbeing is paramount to your success. Don’t sacrifice it for anything, and don’t let the misguided stigma on seeking professional help stop you from doing so.

Put some thought behind how you spend your rest days. There are a number of activities that have been demonstrated to help make your rest more meaningful and others that can make things worse.

We’re sure you already know, but it’s worth repeating: do spend your rest days exercising, reconnecting with loved ones, or just enjoying some quality chill time.

If you choose to spend your rest days binge drinking, eating junk food, or throwing off your sleep schedule, the ramifications will make themselves felt, in your studies and their understanding.

Relax. You’ve got this.

Routine, study schedules, and purposeful relaxation can be the difference between striding confidently into your exam and living under the weight of constant dread and anxiety.

Your mental wellbeing is paramount to your success. Don’t sacrifice it for anything, and don’t let the misguided stigma on seeking professional help stop you from doing so.

What’s needed is a cultural shift where mental health is treated as routinely as the flu or diabetes. As doctors and leaders, you can be the ones to enact this change.

Let that revolution begin with your new routine, study plan, and commitment to resting with purpose.