On July 21, 1969, American astronaut Neil Armstrong became the first person to walk on the Moon.

An extraordinary achievement of scientific willpower and innovation, sheer guts, and generation-defining geo-political intent, it took just over eight years and two months from President John F. Kennedy publicly committing to the idea, to a few footprints in the dust of a lonely world that makes home look like an oasis.

With speed again crucial, the same components and incentives are in place now, as researchers around the world race to find a vaccine that successfully combats COVID-19. The New York Times described it as “arguably the most important scientific undertaking in generations.”

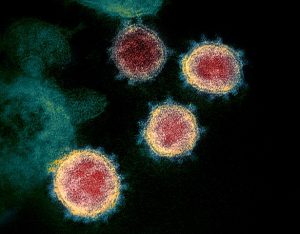

Since its first cases in China in late 2019, more than 11 million COVID-19 cases have appeared worldwide, with more than 500,000 dead from the novel coronavirus.

In the United States, more than 2.8 million have been infected and more than 129,000 have died, making it the pandemic’s worst-hit nation. A standstill of international travel has frozen economies globally, with the hope of post-pandemic social and economic reform tied, in some measure, to the release of an effective vaccine.

“Most people don’t realize that successfully inventing and developing any new drug or vaccine is quantifiably among the hard things that human beings try to do,” George Yancopoulos, the co-founder, president, and chief scientific officer of Regeneron, told the Times.

After a flat-footed start that, by April, saw experts warn against an effective vaccine appearing within 18 months, hopes are now beginning to rise as a number of companies make headway.

Two days ago, the World Health Organization announced that, internationally, 18 potential vaccines are in the clinical evaluation phase. 129 others are in preclinical evaluation.

Most people don’t realize that successfully inventing and developing any new drug or vaccine is quantifiably among the hard things that human beings try to do.

Vaccine trials require three rounds of testing, from phase one to three. The first two are small with hundreds of volunteers tested for vaccine safety and biological activity. Phase three needs tens of thousands of volunteers, ideally globally, to see if the vaccine is effective in all possible scenarios.

“Most vaccine phase three trials need to enroll tens of thousands of patients … you need lots of people to show a statistically significant difference,” Dr. Todd Ellerin, director of infectious diseases at South Shore Health in Massachusetts, told ABC News.

Leading efforts

So far only one possible vaccine—developed by the University of Oxford (in the United Kingdom) and pharmaceutical company AstraZeneca—has officially started its phase three trial.

After promising phase two and three results, Sinovac Biotech’s CoronaVac has emerged as China’s leading potential vaccine finder. This month, it will be tested on 9000 people, in phase three trials, in Brazil.

Phase three trials have yet to begin in the United States, though, after delays, the first Moderna vaccine human trials are likely within the next month. 30,000 Americans will participate in the Moderna trials.

Moderna is one of five American efforts that have been spurred on by Operation Warp Speed, a near-$10 billion cross-agency project to find a vaccine for Americans. Johnson & Johnson has also received funding, as has AstraZeneca.

Despite the resources involved in Warp Speed, some scientists are worried that “tried and true vaccine technologies” are taking a backseat to newer approaches with less proven track records.

“New technologies are good, and they could perform well, but we should really be hedging our bets,” Dr. Saad Omer, an infectious disease expert at Yale, told CNN.

In contrast to the United States, four of the five vaccines that have reached the clinical trial phase in China are using the time-honored approach that sees an inactivated virus draw an immune response from the body. The newer Warp Speed approaches use only part of the virus, or even just its genetic material.

Despite the controversy, some federal officials are confident that a safe vaccine can be found by the end of 2020.

Regardless of where the breakthrough finally comes, finding a successful vaccine is just the first step in making it available to the wider population, and ending the soaring infection rates and death tolls around the world.

Mass production and distribution will undoubtedly have their share of problems while receiving the actual vaccine will depend on where you sit within society.

Though CBS News has reported an independent panel could be set up to decide who receives an effective vaccine first, the CDC says that public health professionals, healthcare providers, pharmacists, emergency service workers, ‘mission essential’ military personnel, pregnant women, and toddlers have the highest priority.

The biggest slice of the American population—healthy adults aged between 19 and 64—are considered the lowest priority.

Setting expectations

Yesterday, the World Health Organization (WHO) announced it expects initial results from clinical trials it has been conducting on drugs that may be able to treat COVID-19 in some patients.

However, Mike Ryan, head of the WHO emergencies program, pumped the brakes on a potential vaccine following an effective drug.

Even if a vaccine showed promise, Ryan said a timeline for mass production would be hard to predict—after all, a SARS vaccine has never been found. As recently as May, he stated that COVID-19 “may never go away.”

Still, there is some hope in the scientific community that progress is being made. In an in-depth investigation that saw them speak to a range of leading vaccination experts, USA Today reported that overall international progress is likely a third of the way toward a “widely available coronavirus vaccine.”

“The sun has not yet peeked over the horizon, but the horizon glows in the East,” Dr. Kelly Moore, the Immunization Action Coalition’s associate director of immunization education, told USA Today. “We are no longer in darkness.”

Dr. Tony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, is hopeful that several vaccines are eventually made available.

The sun has not yet peeked over the horizon, but the horizon glows in the East. We are no longer in darkness.

“I’d love to see more than one vaccine get to the goal line, as it were,” Dr. Fauci told the BBC recently. “The world needs more than one vaccine.”

Expect great financial rewards—and power—to flow to the teams, and countries, that get there first, and a feeling of having reached a far and distant shore, like Armstrong did in 1969.

Like America after Kennedy in 1961, the realities of how it actually plays out remain ahead of us.

“It’s wrong to think that a vaccine will be a ’flick-of-a-switch’ solution that saves the entire world at once,” Dr. Ruth Faden, a Johns Hopkins bioethicist, told HUB last week.

“A vaccine may play a critical role in getting us back to normal, over time, but it will be a slow and layered process, which, as you can see, has many complications.”