While still scarcer than men, a female surgeon is now a common sight in the American military’s operating theaters.

A 2017 study, published in Military Medicine, found that there were 376 female surgeons in the United States Army, Navy, and Air Force, making up 21.5 percent of the overall numbers (the U.S. Navy had the most, with 24 percent women).

Those that serve today can claim a lineage that reaches back to one of the most extraordinary women in American medical history, Dr. Mary Edwards Walker.

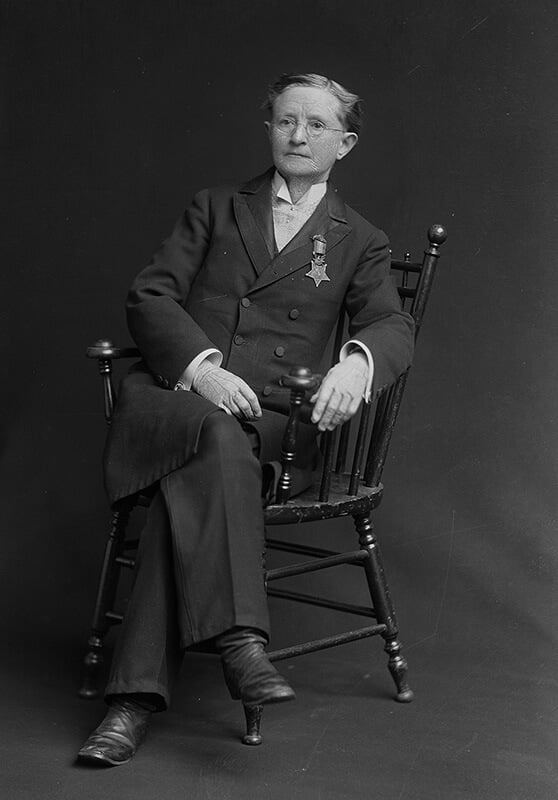

Walker, who’d later become a famed women’s rights activist and lecturer, is the only woman to have ever received the Congressional Medal of Honor, for her service as a surgeon during the American Civil War.

The first female surgeon in U.S. military history, Walker’s decoration was recommended by Civil War icon General William T. Sherman, who had his testimonial signed by President Abraham Lincoln before he was assassinated.

It is a shame that people who lead reforms in this world are not appreciated until after they are dead; then the world pays its tributes.

Likely because of her gender, Walker had the medal, which she proudly wore in public for the majority of her life, stripped away from her in 1917, two years before she died. It was only reinstated by President Jimmy Carter sixty years later.

“Dr. Mary lost the medal,” Anne Walker, a distant relative of the legendary physician told the New York Times in 1977, “simply because she was a hundred years ahead of her time, and no one could stomach it.”

Born in Oswego, New York in 1832, Walker studied medicine at Syracuse Medical College, graduating in 1855 as the only woman in her class. Along with her husband, a fellow med student whom she later divorced, she set up a small private practice in Rome, New York.

The start of the Civil War, in 1861, saw her travel to Washington D.C. to apply to become a surgeon with the Union Army. Turned down because she was a woman, Walker volunteered as a nurse, treating wounded soldiers from the First Battle of the Bull Run.

Her continuing requests would eventually see her serve as a volunteer surgeon at the Battle of Fredericksburg in late 1862, before the Army of the Cumberland, in Tennessee, finally contacted her the following year to serve as the first-ever female surgeon in the U.S. Army, with the 52nd Ohio Infantry.

Despite dramatic advances in medical technology, the overall role of the battlefield doctor was little different in 1863 to what it is today.

“Doctors have a very important role in war: to heal those injured and harmed by conflict,” The Conversation wrote, in 2011.

“The challenges of conflict medicine are different from those in civilian practice and it is imperative that those doctors who intend to serve in war zones endeavor to understand the unique ethical complexity they may face.”

Unlike today (although it still certainly exists), Walker faced constant pressure and judgment due to her gender, but boldly parlayed it with her skill—and dress.

During her service as a military surgeon, Walker dressed like an officer, “having a gold stripe running down the trouser legs, wearing a felt hat with a gold cord, and an officer’s overcoat,” according to the New York Times obituary of her death, in 1919.

“As she always explained it,” the Times continued, “Dr. Walker’s scheme for wearing trousers was but a part of her general and life-long struggle for women’s rights.”

Walker was captured by the Confederates in 1864 and spent four months in a Virginia prisoner of war camp, before being exchanged for an enemy officer. A month after her release, she was back operating on Union soldiers wounded in the Siege of Atlanta.

Though she continued practicing as a physician following the end of the Civil War in 1865, Walker increasingly concentrated on women’s rights efforts.

A long-time crusader for suffrage and dress reform, she became a popular touring lecturer on women’s rights who’d later testify before Congress about the subject. Walker died in 1919, aged 86.

Though more than one hundred years have passed since her death, her legacy has been well preserved.

Amongst other tributes, Whitman-Walker Health, an iconic Washington D.C. community health center focused on LGBT healthcare, is named for her (and poet Walt Whitman), while the U.S. Postal Service celebrated her achievements with a 20-cent stamp in 1982.

More recently, a six-foot, 900-pound bronze statue of Walker was unveiled in her hometown, in 2012. Her beloved Medal of Honor is now held by the Oswego County Historical Society.

“I have got to die before people will know who I am and what I have done,” Walker once reportedly said. “It is a shame that people who lead reforms in this world are not appreciated until after they are dead; then the world pays its tributes.”

Her words do ring true, though the fact that more than one in five U.S. military surgeons are now women shows her courage and dedication which has definitely done its job.

The inevitable increase in those numbers will ultimately be the greatest tribute, of all.