Every ten minutes, another person joins the American national organ transplant waiting list.

Every year, around 8000 people die when organs they require aren’t donated in time.

From former Vice President Dick Cheney (heart) to singer Tina Turner and actress Selena Gomez (kidney), tens of thousands of Americans have benefited from the process over the years. Currently, close to 112,000 are awaiting organ donations. 39,718 received one, in 2019.

Yet, like most other aspects of medicine, the act of giving and receiving a human organ in the United States has its fault lines marked by racial disparity.

“Although minorities are more likely to be diagnosed with kidney failure, they are less likely to be transplanted. The majority of transplants in the U.S. go to whites.”

Despite making up around 60 percent of the national organ waiting list, only around 18,000 minorities—around 45 percent of the list—received an organ transplant.

Of all those on the list, Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) reports 29 percent are Black, 19.8 percent Latinx, and 8.6 percent Asian-American, while other ethnicities make up 2.3 percent.

While they make up just 40 percent of the list, white Americans receive 54.5 percent of all organ transplants, compared to 21.0 percent of Black recipients, 16.8 percent Latinx, 5.1 percent Asian-American, and 2 percent other.

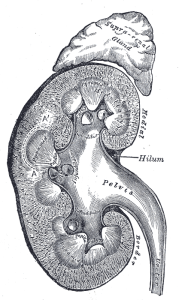

Kidney transplant disparities

When you consider that kidney transplants are required by around 83 percent of the list, those figures become even more shocking (regardless of race, those waiting for kidney transplants can often wait between three and five years to receive one).

According to the National Kidney Foundation, Black Americans suffer kidney failure at nearly three times the rate of their white compatriots.

Latinx and Native Americans have around double the rate, while Native Hawaiians and Polynesian Americans suffered more than eight times worse than white Americans.

“Although minorities are more likely to be diagnosed with kidney failure,” Dr. Camilla Nonterah, an assistant professor of health psychology at the University of Richmond, wrote in The Conversation, last year, “they are less likely to be transplanted.”

“The majority of transplants in the U.S. go to whites.”

The federal stats are matched by public opinion, as shown in the HRSA’s recent National Survey of Organ Donation Attitudes and Practices,

Released in February, the survey is the fourth, and largest, national study of the subject since 1993, polling around 10,000 respondents. It showed that, since 2012, the belief that minorities were less likely to receive transplants has increased from 30 to 48 percent.

“This change … suggests that, since 2012, respondents are much more likely to believe minorities are less likely to get transplants they need because of discrimination,” the report wrote.

Changing laws and improving numbers

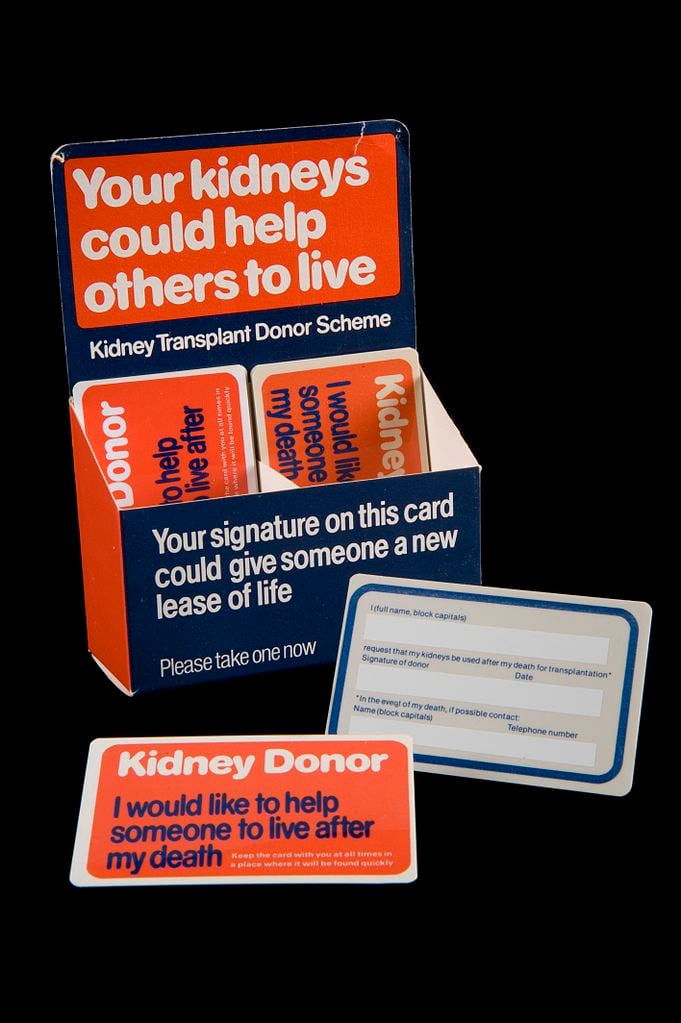

The first organ donation surgery in America occurred in 1954, when Boston’s Dr. Joseph E. Murray led a team, transplanting a kidney from Ronald Herrick to his twin brother Richard.

With the adoption of the Uniform Anatomical Gift Act under President Lyndon B. Johnson, the legal definitions of the practice were first approached in 1964.

Organ donation became a hot topic in the 1980s, following the passing of the Uniform Determination of Death Act at the start of the decade.

Improving a more narrow law written two years prior, the act expanded death to include both the “irreversible cessation of circulatory or respiratory function, or … irreversible cessation of all functions of the brain, including the brain stem.” It had a major impact on the potential availability of donatable organs.

Greater infrastructure was on the way. The Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) was set up under President Ronald Reagan’s Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) in 1984.

“We want all people—regardless of background—to educate themselves on the importance of donation and to register as donors.”

Social security allowances under the existing law saw the expansion of potential organ recipients, whom a national registry was set up for.

In 2006, the Uniform Anatomical Gift Act was passed, making it illegal for others to revoke consent after death, if the donor was legally registered as a donor while alive, further expanding the potential pool of much-needed organs.

Supported by 90 percent of Americans today, an average of 85 organ transplants occur every day in the U.S. Nearly 40,000 transplanted organs last year came from 11,900 deceased and nearly 7,400 living donors (organs from a deceased donor can save up to eight lives).

The overall figures are an 8.7 percent increase from 2018, marking the seventh year of increase, while the national waiting list has decreased yearly from its high of more than 120,000, in 2014.

Continuing challenges

Outside the racial disparities, encouraging recent statistical trends don’t mask the overall challenges. Though still high, public support for organ donations has decreased from 94 percent in 2012, while only around 60 percent of all Americans are registered as donors.

In an initiative to highlight the racial disparities in organ donation, the National Organ, Eye, and Tissue Donation Multicultural Action Group is calling August National Minority Donor Awareness Month. You can register as a donor here.

With only three out of every 1000 people dying in a way that allows for organ donation, the group is encouraging increasing registered numbers across all demographic groups. Last year, 70 percent of all deceased donors were white.

“Transplants can be successful regardless of the ethnicity of the donor and recipient,” Dr. Michael Shullo, associate vice president of transplant services at West Virginia Medicine (WVM), told WVU Medicine News, this week.

“We want all people—regardless of background—to educate themselves on the importance of donation and to register as donors.”