Before 1922, most observations of diabetes in medical history didn’t stretch much further than the acknowledgement of a ‘sweet urine’ that, according to a legendary Roman academic, could make life “short, disgusting, and painful.”

So when Canadian physician Sir Frederick Banting and his American medical assistant Dr. Charles H. Best created insulin in Toronto, treatment of the disease was absolutely transformed, likely saving tens of millions of human lives.

Basically, too few people with diabetes actually know the true story of how insulin was discovered.

Yet while insulin has been described as “arguably the greatest medical miracle of this century,” the scarcely believable story behind its discovery is not well known.

Guided by a great research partnership that started with the toss of a coin, and ended with a plane crash, it weaves its way from post-World War I Toronto to Stockholm, where a Nobel Prize in medicine was, most likely, unjustly awarded.

With the daughter of a United States Supreme Court Chief Justice, a far-right Romanian scientist, who—but for the War—may have actually beaten Banting and Best to insulin, and a dog called Majorie, the supporting cast suits the ride.

“The story is fundamentally dramatic – it is both a race against time, and a parable about friendship, animosity, human imperfection, chance, and the nature of human endeavor,” Neil Fleming, an English writer seeking to produce a film on part of insulin’s discovery, told Healthline.

“Basically, too few people with diabetes actually know the true story of how insulin was discovered.”

Diabetes now, and then

Though it does indicate the improving powers of medical observation and research from the 6th century BC onwards, diet is probably a significant reason diabetes was rare in antiquity.

With added sugars making up 14 percent of the average American’s daily calorie intake (the recommended limit is 10), it is widespread now.

This year, the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported that more than 120 million Americans suffer from either prediabetes or diabetes. Around 34.2 million (10.2 percent of the overall population) are likely to have either type 1 or 2 diabetes, which was the seventh leading cause of death in the U.S, in 2015.

“More than a third of U.S. adults have prediabetes, and the majority don’t know it,” Dr. Brenda Fitzgerald, then the CDC’s director, said, in 2017.

“Now, more than ever, we must step up our efforts to reduce the burden of this serious disease.”

The first references of what was likely diabetes were made by Egyptian scholars around 552 BC, with Chinese and Indian academics observing diabetes mellitus around the same time.

…an affliction that is not very frequent … being a melting down of the flesh and limbs into the urine … life is short, disgusting and painful.

All noted that those suffering from diabetes endured a constant flow of ‘sweet urine.’ In the 1st century BC, Rome’s Demetrius of Apameia is credited in introducing the term ‘diabetes,’ which is derived from the Ionic meaning to ‘pass or run through.’

In the 2nd century AD, Areteus of Cappadocia wrote ‘what is considered the first accurate clinical description of diabetes.’

The rare illness, he observed, was “an affliction that is not very frequent … being a melting down of the flesh and limbs into the urine … life is short, disgusting and painful … thirst unquenchable … the kidneys and bladder never stop making water … it may be something pernicious, derived from other diseases, which attack the bladder and kidneys.”

Though Indian academics were able to differentiate what we now recognize as type 1 and 2 diabetes by the 5th century AD, ancient Roman research “dominated most of the prevailing concepts of diabetes as a disease of the kidneys over the next 1500 years.”

The race to discover insulin

The discovery of insulin had its real roots in the 1770s, when English physician Dr. Matthew Hobson showed that ‘sweet urine’ was caused by sugar, and ‘preceded and accompanied by sugar in the blood.’

German research around the pancreas, especially the sugar-regulating islets of Langerhans, in the late 19th century set the stage for the race to develop insulin in the coming decades.

The son of an Ontario farmer, Banting was a Toronto orthopedic surgeon who lectured part-time at the University of Toronto, when he started seriously researching the pancreas in 1920.

Banting recruited the help of Professor John Macleod, the University’s head of physiology, who would grant him lab space, ten dogs for experimentation, a research assistant— Best, then a 21-year-old medical student from Maine—and guidance and advice whenever it was required.

Amazingly, Best’s involvement in the research had been decided by the flip of a coin.

In the summer of 1921, he and fellow student Edward Clark Noble tossed for who would help Banting for the first month of his work. Best won.

His easy friendship and professional connection with Banting meant Best stayed on, consigning Noble, who played a small but important role in the discovery of vinca alkaloids, to the dustbin of medical history.

Nicolae Constantin Paulescu would join him, despite making gigantic strides in isolating a substance that would include insulin, in the preceding decade.

By 1916, Paulescu, a Romanian scientist, had isolated an aqueous pancreatic extract that, when injected into diabetic dogs, reduced sugar levels.

Calling it ‘pancreine’, his research was put on hold for several years after he was drafted into the Romanian Army for World War I. The delays would prove costly for Paulescu, a proto-facist who engaged in anti-semitic hate speech.

Success, fallout, and the Chief Justice’s daughter

Bunting and Best’s insulin work began in earnest at the University of Toronto in May 1921.

“They first tied off the pancreatic ducts of dogs; after several weeks, they removed the atrophied pancreas and created an extract, which they injected into the vein of a sickly dog named Majorie, whose pancreas had been removed several days earlier,” Dr Siang Yong Tan and Dr. Jason Merchant wrote in an engaging 2017 article on Banting.

After an hour, there was a noted change in the dog’s demeanor. It was able to raise its head, stand and even wag its tail. There was a dramatic decrease in the dog’s blood sugar levels.

“After an hour, there was a noted change in the dog’s demeanor. It was able to raise its head, stand and even wag its tail. There was a dramatic decrease in the dog’s blood sugar levels. Since the extract of islet cells was the cause of this reversal, Banting named it ‘isletin.’

After some setbacks, the pair began to use isletin from calf embryos to greater success, with biochemist J.B. Collip bought in to help purify the isletin for human use. Though Banting and Macleod would fall out over the professor’s questioning of the data, insulin had essentially been discovered.

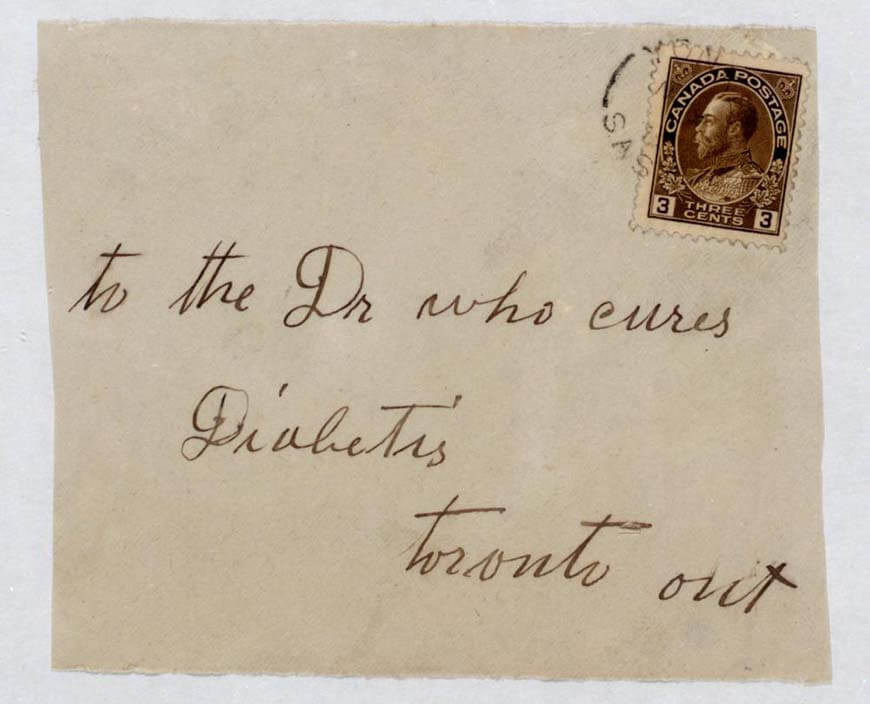

Before insulin was first used on a 14-year-old Toronto boy on January 11, 1922, treatment of diabetes was extremely limited.

Though hardly a long-term solution, fasting and starvation diets were seen as the only option. American teenager Elizabeth Hughes was one of those using ‘starvation’ treatment.

Struggling with what we would now recognize as Type 1 diabetes, Elizabeth dropped to just 45 pounds in 1922, aged 14.

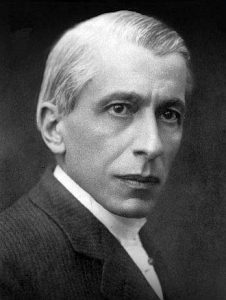

Elizabeth was the daughter of Charles Evans Hughes, one of the most prominent American public figures of the early 20th century.

A former New York governor who’d served on the U.S Supreme Court, Hughes was the Republican candidate for President in 1916, losing one of the closest elections in American history. He would later become a Secretary of State, and the Supreme Court’s Chief Justice between 1930 and 1941.

Elizabeth’s mother convinced Banting to make her one of the first Americans to receive insulin in August 1922, with regular injections ensuring her weight, and health, returned by the end of the year.

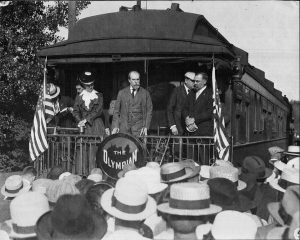

Though Hughes’ treatment would gain public notoriety in the United States, international medical fame would follow for Banting the following year with the awarding of the Nobel Prize in Medicine.

Despite his minimal role in its development, Macleod, a Scot, would also receive a Nobel Prize for the discovery of insulin, further deepening the divide between him and Banting, while the efforts of Best and Collip weren’t recognized.

[Macleod’s awarding of the Nobel Prize in medicine] created a controversy that endures to this day as to who should have really earned recognition for the discovery.

“It created a controversy,” Dr. Simon Murray wrote for HCP Live, “that endures to this day as to who should have really earned recognition for the discovery.”

Banting initially refused the award, later sharing his prize money with Best. Macleod would do the same with Collip.

Despite publishing his findings in France eight months before Banting and Best’s discovery, Paulescu’s research on insulin has largely been forgotten. His far-right political views have further tarnished his legacy.

Mass production, and further development

Banting was given the commercial rights to produce insulin, donating them to the University of Toronto for a dollar in hopes of making the treatment affordable for diabetes sufferers.

After initial struggles, Indianapolis’s Eli Lily And Company, now an American pharmaceutical giant, was approached to improve the process, in turn developing an “isoelectric precipitation” approach that led to mass insulin production.

Though issues with dose standardization persisted in the early days, by the mid 1930s, insulin proportions, still sourced from animals, were able to increase or decrease the length of their effects.

Later marrying Ford Motor Company’s general counsel, Elizabeth Hughes Gossett received an estimated 42,000 insulin shots during her life, dying in 1981, aged 72. It is reported she spoke little about her illness, through her adult life.

The synthesizing of the first human insulin molecule in 1978 would ultimately lead to human insulin four years later.

Further work around the amino acid sequences in human insulin helped create quicker-acting, long-lasting products, later leading to insulin pens and pumps that had a greater impact on those suffering from type 2 diabetes.

Despite Banting’s initial $1 donation, access and affordability of insulin remain a huge issue today. Thanks to a combination of government health regulations, insurance policy issues, and big pharma power, insulin vials regularly cost most Americans around $300.

The legacy of the insulin pioneers

The pioneers of the discovery are long gone, now.

Banting, who is still considered a Canadian national hero today, died in a plane crash in remote Newfoundland in February 1941, aged 49. Paulescu died in 1931, Macleod four years later.

Best was the last, in 1978. Despite their fates being separated by the toss of a coin, he and Noble fell out in the years directly following wild tale behind insulin, rarely to speak again.

“We must not imagine that insulin is able to cure diabetes,” Banting said, in his Nobel Prize acceptance speech in 1923.

“How could that be possible if the cause of diabetes is to be found in the fact that the cells within our organism that produce the hormone necessary for the combustion of sugar are definitively destroyed?

“But insulin gives us the possibility of transforming the severe form to a mild one and thereby restoring his capacity for work and a comparative state of health to the hopeless invalid who, despite the most trying and rigorous restrictions in diet, is constantly threatened by a fatal state of poisoning.”